The history of science has its share of biological frauds, cases where people fabricated an imaginary organism and passed it off as real, or lied about an organism's behaviour. Every now and then, however, a creature that is suspected of being a hoax turns out to be real.

Sometimes, an organism that was once classed as a myth or a cryptid turns out to be an authentic, living creature. But in these cases, scientists or members of the public believed that the discovery was a deliberate fraud.

1. Platypus

Photo by Matt Chan (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The platypus is probably the most famous case of an animal that was, at one time, believed to have been a hoax. And really, who can blame the British scientists who first saw a platypus pelt for being a bit sceptical? The 18th century had seen people try to pass of the remains of mermaids and hydras, so when Captain John Hunter sent a platypus pelt from Australia in 1798, some scientists figured it had to be the work of a creative taxidermist who had sewn bits of duck to a beaver's skin. The surgeon Robert Knox tried to debunk the platypus "hoax" by snipping into the creature's pelt, searching for any stitches that would indicate the animal was a fraud. Of course, he found none, and eventually more platypus pelts and descriptions of the animal followed.

2. King of Saxony Bird-of-Paradise

Can an animal be too striking to be real? The incredible brow plume of the King of Saxony Bird-of-Paradise made it immediately suspect. The New Guinea bird first turned up in a European museum in the late 19th century, and when the Director of the Dresden Museum first described the bird to British ornithologist Richard Bowdler Sharpe, Sharpe declared that such a bird could not possibly exist in nature. Despite his initial suspicions that the bird was the work of a taxidermist, Sharpe eventually eventually saw specimens with his own eyes and was convinced that the King of Saxony Bird-of-Paradise and its remarkable plumage were, in fact, real.

3. Okapi

Photo by Derek Keats (CC BY 2.0)

For European and American researchers who were investigating the wildlife of Central Africa at the turn of the 20th century, the okapi was, for some time, a cryptid. Reports of a donkey-like animal with zebra stripes first reached European eyeballs in the late 19th century thanks to reports from Henry Morton Stanley (who is perhaps best known to modern readers thanks to his search for David Livingstone and allegedly greeting the missionary-explorer by saying, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume.").

In 1900, Dr. P.L. Sclater, secretary of the London Zoological Society, exhibited a pair of "bandoliers" that he was told had been made by soldiers from the skin of an unknown animal. Sclater determined that the hairs were similar those of giraffes and zebras, although he had never seen a skin quite like that one before. The exhibition caused a sensation, with many wondering if the skins were a mere hoax. After all, how had such a creature gone undetected for so long? The following year, the question was settled when Harry Johnston sent the remains of an okapi carcass to London.

4. Pelican

Photo by Tambako The Jaguar (CC BY-ND 2.0)

When Carl Linnaeus was trying to catalogue flora and fauna in his Systema Naturae, he had to take a sceptical view of the organisms he was told about. After all, he was trying to create a taxonomy of living things. Mythical animals and hoaxes were included in the catalogue, but Linnaeus tried to contain them under the heading Animalia Paradoxa.

One animal that Linnaeus initially suspected was a tall tale was the pelican. To be fair, Linnaeus had good reason to doubt the reports from sailors who had spotted the birds in the New World. Linnaeus was told that an adult pelican would deliberately injure itself so that its offspring could drink its blood. It's not true; chances are the myth arose from a misinterpretation of actual pelican behaviour. But that alleged behaviour landed the pelican in the Animalia Paradoxa section of Systema Naturae, at least for a while.

5. Microorganisms

Crop of portrait of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek by Jan Verkolje, via Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine that you're a 17th-century scientist and someone comes and tells you that there are microscopic creatures everywhere, unseen by the naked eye. You might have doubts. The Royal Society of London certainly did in 1676 when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek reported on the "animalcules" he had seen beneath his microscope. In fact, members of the Royal Society suspected Leeuwenhoek of fraud. He ended up sending the society the testimony of several eyewitnesses who had seen the "animalcules" themselves before he was finally admitted to the Royal Society of London and the Society accepted the existence of microorganisms.

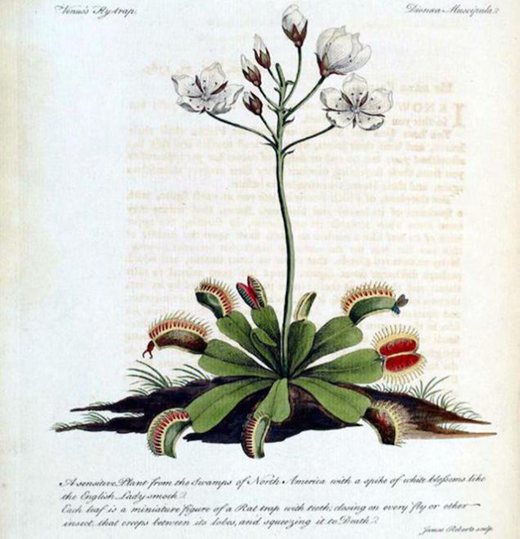

6. Venus Flytrap

Plate from John Ellis' "A Botanical Description of the Dionoea muscipula," via Wikimedia Commons.

Naturalist Sy Montgomery notes in The Wild Out Your Window that when Europeans first heard of the Venus Flytrap in the mid-18th century, many believed the descriptions were a hoax. Here was a "sensitive" plant in a far away land that didn't just sense the movement of animals; it ate them. The first known written account of the plant was made by North Carolina Governor Arthur Dobbs in 1759, and Dobbs showed his specimen to the horticulturists William and John Bartram. It's the naturalist John Ellis who is most closely associated with the Venus Flytrap, however, since he was the one who described the plant in a letter to Carl Linnaeus.

Of course, scepticism about these exotic plants is healthy. Otherwise, you have people believing that there are human-eating trees in Madagascar.

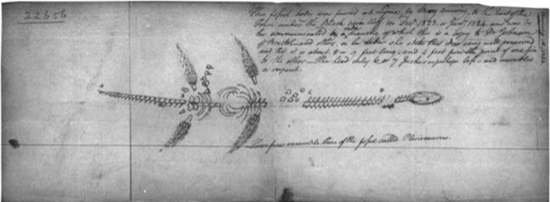

7. Plesiosaurus

Mary Anning's sketch of a Plesiosaur, via Paleonerdish.

In 1823, palaeontologist Mary Anning discovered the first complete skeleton of Plesiosaurus in Lyme Regis in Dorset county. But not everyone believed that the find was genuine at first. The anatomist and palaeontologist Georges Cuvier thought that Anning was a very clever anatomist herself, but believed, given the proportions of the neck, that the creature was a composite made from the skeletons of multiple animals. It took a bit of convincing from fellow palaeontologists William Buckland, Mary Morland, and William Conybeare for Cuvier to accept the marine reptile as a genuine prehistoric animal.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.