One of the problems with having a population as large as 7 billion people (and rising) is that it takes a lot of water to keep everything running. We use water to drink, make food, create energy, manufacture products, extract raw minerals from the Earth and everything else in between. The average family of four can use 400 gallons of indoor water or more every day, to say nothing of the massive quantities of water used by businesses, farms and industry. The driver of our civilization, electricity, is generated by turbines using massive amounts of water; about half of the total water use in the U.S. is by power plants.

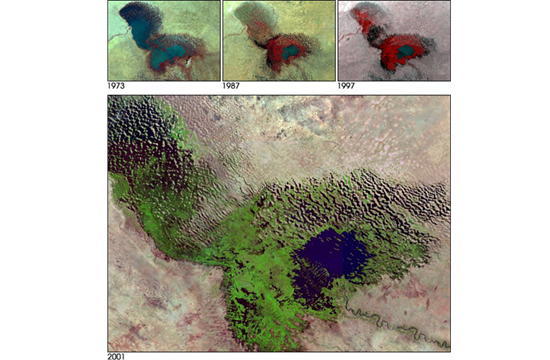

All that water has to come from somewhere, and it shouldn't be surprising to learn that there are a lot of places around the world that are literally drying up (like the Aral Sea, top image). It's never been harder to be a large body of water. In the face of warming temperatures caused by climate change on top of increased demand, some of the world's largest lakes, rivers and seas are growing smaller with every season.

When we use more water than is naturally put back into the system, we draw down the overall supply. That simple equation is the brutal reality of the following dried-up lakes, rivers and seas.

1. Lake Poopó

Lake Poopó was once Bolivia's second largest lake but is essentially dry now. The left side of the image was taken in April 2013 and shows the lake with some water remaining. When NASA trained the Operational Land Imager on the Landsat 8 satellite in January 2016, the space agency was met with a dried-up lake bed, featured on the right side of the image. Drought, climate change and diverting water from the lake's primary source of water are largely credited with contributing the Poopó's decline.

While not terribly deep - it's only about 9 feet to the bottom - Lake Poopó played an important part in local living and wildlife. About two-thirds of the 500 or so families in the surrounding area, many of which survived by fishing in the lake, have already left the area to seek out a living elsewhere. Meanwhile, fish have died by the millions and roughly 500 birds, including flamingos, have also died due to the dried up lake.

2. Colorado River

The Colorado River (seen here from Page, Arizona) used to run all the way from Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado through four other states and parts of Mexico before emptying into the Gulf of California (a.k.a. the Sea of Cortez). Today, the waters run dry long before they reach the historic river mouth, having been pulled and diverted by the states to grow crops, hydrate towns and cities, water lawns and fill up pools. Anything left over at the border between the United States and Mexico - and there rarely is much - is what's left for Mexico. Often the little water that is left is polluted with run-off from farms in the U.S. A multi-year drought has greatly reduced the amount of rainfall feeding the Colorado River, even as demand for its waters has grown, a situation guaranteed to pull the dry mouth of the river even farther up stream.

3. Aral Sea

The Aral Sea is the poster child for large, dried-up bodies of water. If you travel to the Aral Sea, which sits on the border between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, you'll find a disconnected collection of small ponds of sea water sitting in a dusty bowl that held what used to be one large body of water. The Aral Sea, which is technically a lake, has been steadily shrinking since the 1960s when the Soviet Union began to divert rivers that feed the Aral Sea for agricultural irrigation. With the receding waters went a large fishing industry, leaving high rates of unemployment and fishing boats left to dry on the former shoreline.

In recent years, there have been efforts to divert more water back into the sea, but it's unlikely that it will ever regain its former size and glory. The Aral Sea is easily one of the biggest human-caused environmental bungles in history.

4. Lake Badwater

At least humans can feel less guilty about one shrinking lake. The only thing causing Lake Badwater to shrink is good old Mother Nature. Lake Badwater is actually a seasonal lake that appears after rain storms before quickly evaporating once the drops stop falling. Lake Badwater is located in California's Death Valley and at 282 feet below sea level, is the lowest point in North America. Interestingly enough, the highest point in the contiguous 48 states is located only 85 miles away at Mount Whitney. (Check out the super hard-core Badwater Ultramarathon which goes from Badwater to Whitney on a 135-mile course.) With temperatures that can soar above 120 degrees F and almost no humidity, any moisture that gets left behind after a storm quickly dries up, so much so that even a 30-mile-long, 12-foot-deep lake would have trouble staying ahead of the yearly evaporation.

5. Lake Chad

Photo: NASA Earth Observatory

Lake Chad gives the Aral Sea a run for the money in the category of big-but-now-dry bodies of water. According to the United Nations, the lake has lost as much as 95 percent of its volume from 1963 to 1998. The shallow lake (it's only 34 feet deep when full and currently averages just less than five feet in depth) has been hit hard by changes in rainfall patterns, overgrazing, deforestation and increased demand by the surrounding populace. The lake almost dried up in 1908 and again in 1984. Aside from the environmental disruptions, the drying lake is also brewing up trouble between regional governments fighting over rights to the dwindling waters.

6. Owens Lake

Photo: NASA Earth Observatory

Until the beginning of the 1900s, Owens Lake in the eastern Sierra Nevada was a robust body of water up to 12 miles long and 8 miles wide with an average depth of 23 to 50 feet. In 1913, the waters that fed into Owens Lake were diverted by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) into the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Water levels quickly dropped in Owens Lake until they reached current levels - mostly dried up. Today, Owens Lake is a shallow (just three feet deep), much-reduced shadow of its pre-diversion self. LADWP shallowly floods 27 square miles of dried-up lake bed to reduce the number of dust storms, which can cause respiratory problems for nearby residents.

7. Lake Powell

Lake Powell, on the border of Arizona and Utah, was created by the construction of Glen Canyon Dam along the Colorado River. The dam, which was completed in 1963, is 710 feet high and didn't fill up until 17 years after it was completed.

When the region needed to solve a long-running water dispute, Glen Canyon Dam was chosen by the U.S. government after David Brower of the Sierra Club suggested it was a better location than the government's choice of Echo Park, Colo. Unfortunately, Brower made the suggestion before actually seeing Glen Canyon. Despite efforts to overturn the decision, the dam was constructed and miles of canyons, streams, and archaeological and wildlife habitat were swallowed up by the waters.

Today, Lake Powell is a recreational area - and ironically, low lake levels are hurting tourism. One of the small bright spots in a bad situation is that some of the previously submerged sites are seeing the light of day again. (It's too bad it took an ecological crisis to return the land to its natural state, even temporarily.)

8. Lake Mead

In slightly longer than a decade, Nevada's Lake Mead - which sits down river from Lake Powell on the Colorado River - has seen its total volume drop by more than 60 percent. Persistent drought and increased demand have wreaked havoc on water levels, sometimes draining three feet of depth in a month. Now, the lake is listed at about 1,100 feet above sea level, a foot below the previous all-time low set in 1937. With demand not letting up and climate change warming things up, it doesn't look good for Lake Mead. Water managers have the option of releasing water from Lake Powell to raise Lake Mead, but that doesn't solve the problem of not having enough water in the system in the first place.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please adhere to proper blog etiquette when posting your comments. This blog owner will exercise his absolution discretion in allowing or rejecting any comments that are deemed seditious, defamatory, libelous, racist, vulgar, insulting, and other remarks that exhibit similar characteristics. If you insist on using anonymous comments, please write your name or other IDs at the end of your message.